Commission greenlights infra-focused IPCEI project

15 February 2024

Hydrogen Europe manifesto puts energy transition front and centre

20 February 2024Hydrogen’s role in Europe’s net-zero economy will be substantial and multi-faceted. The large pile of directives and regulations, with specific provisions for the molecule and its derivatives, makes this clear. However the extent of its involvement in each sector is still being debated and market projections, rigorous as they may be, can only guide us so much in what is a dynamic and fast growing market.

The REPower EU targets for green hydrogen by 2030 include 10 million tons (Mt) of domestic production and 10Mt imported internationally from multiple global partners. A report from Transport & Environment (T&E) this week (13 Feb), entitled ‘Hydrogen Hype: Why the EU should be cautious about uncertain imports from far-flung places’, asserts that there is a disconnect between Europe’s hydrogen ambitions and the real potential, particularly when it comes to imports – ultimately asserting that there is no case for hydrogen trade. Hydrogen Europe welcomes a robust debate on these matters, and believes that there is both demand for hydrogen imports and a large potential supplier base, which can effectively address the challenges associated with hydrogen development and seize this opportunity to accelerate socioeconomic development.

First, hydrogen imports will be an important element to meet EU’s decarbonization and energy security goals. According to the T&E report, there will only be a demand of around 4Mt by 2030, which could be met by European production alone, eliminating the need for imports. This calculation is based on the binding targets in EU legislation relating to industry and transport, which crucially are minimum targets.

But the project pipeline already far outstrips the legal minimum. According to Hydrogen Europe’s Clean Hydrogen Monitor 2023, which tracks the European project pipeline, there are already projects accounting for 7Mt worth of demand in the project pipeline for 2030, and that is only in industry. When including all relevant sectors; industry, agriculture, maritime, aviation, road mobility, and storage, there is a defined demand of between 8Mt and 10Mt of hydrogen and ammonia projects for 2030.

The acknowledgment in the report that “different results could appear in the long-term” if these sectors were included and projected over a longer time frame is notable, as demand projections for after 2030 are pertinent to the discussion. For instance, the European Commission published its Communication setting EU targets for the reduction of greenhouse gases emissions by 2040, and expects production of 20 to 35 million tons (Mt) of renewable-based hydrogen, depending on the chosen scenario. This would represent up to 10% of the final energy demand, increasing to at least 16% by 2050. In fact, this only accounts for pure hydrogen. By adding e-fuels – which are made from hydrogen – to the equation, the share rises to 12.4% and 24.1%, respectively, demonstrating the fundamental role it will play in the energy transition.

In this context, the EU will be one of the main demand centres in the world for clean hydrogen imports, alongside countries in East Asia like Japan. Critically, certain regions in Europe will face supply shortages to meet their binding hydrogen targets but benefit from access to the sea and good port infrastructure. Regions in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany or Poland, among others, have significant demand for renewable hydrogen and ammonia to decarbonise their industry, outstripping their expected 2030 supply. With all of them boasting large international maritime or inland ports, they will look to imports as a solution.

Second, there is a large potential list of suppliers to the European Union. The T&E report selects Chile, Egypt, Morocco, Namibia, Norway, and Oman in its analysis as the most likely exporters to Europe. It finds that projects announced in 2022 across these six countries only totalled 3.9Mt of renewable hydrogen potential capacity by 2030, with only 2.6Mt of those available for export to the EU. There is nothing wrong with this calculation, but the selection of realistic potential hydrogen trading nations is longer than these six.

The United States, which has famously bet big on hydrogen with its Inflation Reduction Act, is gearing up to be a global exporter with significant demand incentives but a lack of demand targets. The country is targeting its own 10Mt of clean hydrogen capacity by 2030, and around 3Mt could be destined for European shores. With unencumbered access to both the Atlantic and Pacific markets, it is also strategically placed to benefit from a hydrogen export strategy. The US’ neighbour Canada is also expected to play a big role in global hydrogen trade. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia, which saw the largest project financing for green hydrogen close last year, completes the Middle Eastern contingent along with Oman and Qatar. The North America and MENA regions in general should be identified as key exporters in the hydrogen trade network and included in any projections on the matter.

Challenges associated with hydrogen development must be put into perspective and can be efficiently addressed. When discussing the six selected countries in its report, T&E addressed the topic of water use and the very real issue of water scarcity in some of these countries. Electrolysis, famously, involves splitting water molecules to create hydrogen. Water is indeed the primary feedstock in electrolysis, but the image of “80-120 thousand Olympic swimming pools” of water needed for the six to produce the 2.6Mt of green hydrogen for Europe requires some perspective.

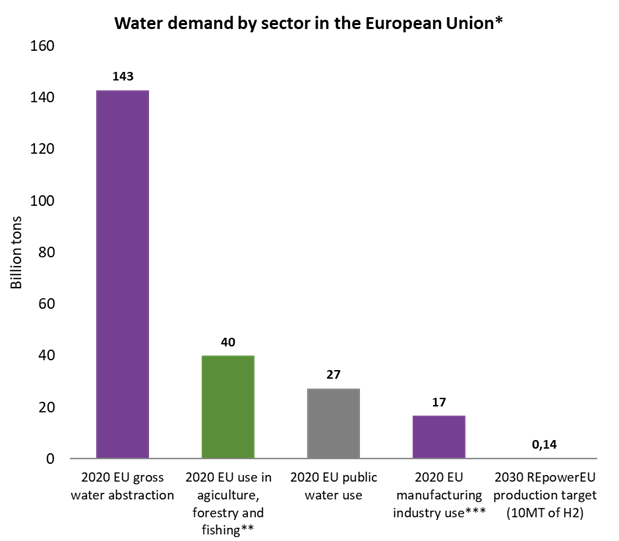

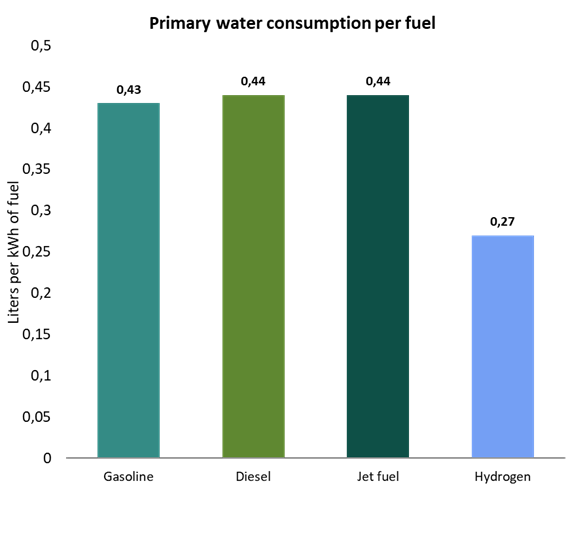

Water consumption in the electrolysis process is around 40% less per kWh of fuel than that used by gasoline or diesel (0.27l/kWh vs 0.44/kWh), the fuels hydrogen is intended to replace. Therefore, transitioning from fossil fuels to hydrogen would represent a substantial net saving in water use. Comparatively, the total water volume potentially used in clean hydrogen production is relatively insignificant; if the EU were producing 10Mt of green hydrogen the estimated 0.14 billion tonnes of water needed constitute 0.00098% of the EU’s 2020 gross water abstraction (143 billion tonnes).

There is growing and encouraging research and investment into the use of desalinated water for hydrogen production, which further alleviates water stress and can even have a substantial positive impact on regional water management. The additional cost is negligible and the risks associated with desalination – another issue rightly raised by T&E – can be comprehensively mitigated with a number of sustainable solutions for treatment or disposal.

Finally, for many countries, hydrogen development represents an important socioeconomic development opportunity that goes far beyond trade. Fostering win-win partnerships, from the industry and the institutional perspective, is a fundamental tool to ensure hydrogen is not done for export to the European Union only, and brings value to local populations. As assessed in a new UNIDO, IRENA, IDOS report, hydrogen production in developing and emerging economies would, besides help to decarbonise their economies, create domestic value and jobs while improving energy security.

All in all, the European Union will benefit from a clear, realistic, and fair international hydrogen trade strategy, paving the way for the emergence of a global market for clean molecules that will be essential to decarbonising European and global economies and meet the 2030 and, critically, 2050 goals of the Paris Agreement. With Europe currently at the centre of global demand, it is preparing now for a global trading network that provides for all.